The last conversation I had with my son was about something stupid. He called me on a Sunday evening to ask if I still had his old hoodie somewhere in my closet. I told him I probably did, buried under a decade of “I’ll sort this later.”

He laughed and said, “It’s okay, Mom. I’ll dig for it next time I come over. I just remembered it today for some reason.”

Two days later, he was gone.

And three days after his funeral, his boss called me and said, “Ma’am, I’ve discovered something you need to see.”

My name is Margaret Lewis. I’m 63 years old and I am the mother of exactly one child. His name is Daniel. This is the story of how I lost my son and then found out who he really was when it was already too late.

Before I tell you what his boss showed me—before the emails, the recording, and the truth that ripped me open all over again—I want to ask you something.

If someone you loved died and then a stranger called you from their job and said, “I found something you need to see,” would you answer? Would you go? Or would you be too afraid of what you might learn?

Tell me in the comments. I know that sounds like a YouTube thing to say, but I mean it. There’s a strange kind of comfort in knowing how other people handle the unthinkable. And if stories like this, real messy emotional stories about family, work, and the quiet courage of ordinary people, speak to you, please subscribe and turn on the notification bell. There are a lot of mothers like me whose stories never leave the kitchen table. Maybe one of them is yours.

All right. Let me start where my life used to make sense.

I grew up in a town nobody moves to on purpose. Row houses, old factories, a river that smelled like metal in the summer and ice in the winter. My father worked at the steel plant before it closed. My mother cleaned offices at night. We were poor, but it wasn’t the kind of poor that makes the news. It was the kind where you learn very early to count every dollar and say thank you for secondhand things.

I got married at 22 to a man named Robert Lewis. He was quiet, solid, the kind of person who fixed things that other people threw away. We were not romantic in the way movies are romantic, but we were kind to each other. And after the childhood I’d had, that felt like a luxury.

We tried for children for almost six years. By the time I held Daniel in my arms, I was 30, exhausted, and convinced that somehow the universe had made a clerical error and given me a miracle it meant to send somewhere else.

He was a serious baby, almost suspicious. He’d stare at people like he was trying to figure out their motives, even before he could talk. When he finally did talk, he never really stopped.

“Why does the moon change shape?”

“Where does the bus go when it’s not on our street?”

“If you work all day and Daddy works all day, who’s watching the house?”

I answered every question as best I could. When I didn’t know, we looked it up in the old encyclopedia set my father had rescued from a dumpster when an office downtown upgraded to computers.

I didn’t have much, but I had two things I could give my son: love and the absolute unwavering belief that education would open doors for him that had been locked for me.

I worked in a grocery store by day and cleaned houses on weekends. Robert worked in a machine shop. We took overtime shifts. We saved. Not for vacations, not for new cars—for Daniel. For textbooks and shoes that fit and SAT prep classes we could barely afford but paid for anyway. Because my son was not going to live and die without ever leaving this town.

He did his part. He studied. He stayed out of serious trouble. He got a scholarship to a state university and a part-time job in the campus IT department. He majored in computer science.

“Because that’s where the money is, Mom,” he told me, grinning, when he walked across that stage in a blue gown and shook the dean’s hand.

I clapped so hard my hands hurt. Robert cried openly.

“Remember this,” I whispered as we hugged him afterwards. “You did this. Nobody can ever take this away from you.”

“I will,” he said. “I promise.”

He kept that promise longer than I ever knew.

After college, Daniel got a job at a company called North Bridge Data Solutions. It was one of those office parks on the edge of the city you only notice if you work there. Glassy buildings, identical trees, a parking lot full of cars that cost more than our house.

“They do cloud infrastructure stuff,” he explained when he first told us about it. “Storage systems, that kind of thing. Boring if you don’t like computers. Good benefits.”

The day he started, he sent me a picture of himself in a button-up shirt and slacks.

Look at you, I texted back. You look like you’re about to sell someone a very serious policy.

He replied with a laughing emoji and a photo of his desk. Two monitors, a generic black keyboard, a mug that said “Northbridge” in blue letters.

This is where it starts, Mom. No more overtime at the machine shop.

For the first couple of years, things were normal. He worked long hours, but not insane. He’d call on his commute home, tell me about funny things his co-workers said, vent about a bug that wouldn’t fix itself. I didn’t understand half the technical words, but I understood the tone. He was proud. He was building something. He was, in his mind, finally doing what I told him his whole life school would let him do: move up, out, away.

Then Robert got sick.

Pancreatic cancer is a cruel thief. It does not sneak. It breaks down the door and takes everything. In less than a year, the man I’d shared a bed with for three decades went from grumbling about the price of tires to lying in a hospital bed in our living room. His skin yellowed, his hands shaking as he tried to hold my fingers.

“I hate leaving you like this,” he whispered once when Daniel had stepped out to talk to the hospice nurse.

“You’re not leaving me,” I said, even though we both knew that was a lie. “You’re just going ahead. Save me a good chair, okay?”

He smiled weakly.

“Bossy,” he said. “Even now.”

He died on a Tuesday morning while the birds outside were making more noise than the traffic.

After the funeral, Daniel stayed with me for a week. He fixed the leaky kitchen faucet, cleaned out the garage, replaced the porch light that had been flickering for months. He set up automatic payments for the utilities so I wouldn’t have to remember due dates.

“Your only job now,” he said, “is to keep the plants alive and watch that true crime show you like. Let me worry about the rest.”

“Daniel,” I said, “you have your own life.”

He shrugged.

“You’re my life, too,” he said simply.

He started sending me part of his paycheck every month.

“Don’t argue,” he said the first time I protested. “Consider it rent for all the food I took out of your fridge between ages 0 and 18.”

I laughed, but my chest hurt. I knew what it meant for him to send that money. I also knew that if I refused, he’d just find a more complicated way to get it to me. So I put it in an account and used it for property taxes, medication, small repairs. I didn’t touch my pride with it—or at least I told myself that.

The first sign that something was wrong at North Bridge came in the form of silence.

Daniel used to talk about work at least a little. Nothing confidential, obviously, but enough that I knew names.

“Tom on my team did this.”

“Marissa cracked that bug.”

“Mr. Harris wants us to finish the roll out before the end of the quarter.”

Then one day the story stopped.

“How’s work?” I asked during our usual Wednesday call.

He paused.

“Fine,” he said. “Busy.”

“Busy good or busy bad?” I pushed.

“Just a lot of pressure,” he replied. “They’re restructuring some things. New upper management. You know how it is.”

I didn’t. I’d never worked anywhere with upper management. My bosses were always close enough to smell their lunch on their breath. But I knew what pressure looked like.

“It’s not worth your health,” I said. “No job is.”

He laughed, but it sounded thin.

“Mom, I’m okay,” he said. “Really, don’t worry.”

Of course I worried. That’s what mothers do. We worry when there’s something to worry about and when there isn’t, just in case.

Over the next few months, I noticed changes. He called less often. When he did, he sounded tired, like his voice was carrying extra weight. Sometimes, I heard keyboard clicking in the background, even at 9 or 10 at night.

“Are you still at the office?” I asked once.

“Yeah,” he said. “We had a situation. I’ll tell you about it when it’s over.”

He never did.

One Saturday he came over for dinner and I saw dark crescents under his eyes.

“You look like I used to look after Christmas week at the store,” I said. “Are they paying you three salaries?”

He smiled weakly.

“I wish,” he said.

We watched a movie. He fell asleep halfway through on the couch, his head tilted back at an uncomfortable angle, mouth slightly open. He looked like he had when he was 16 and refused to go to bed before finishing a video game.

I covered him with a blanket and stared at the blue light flickering across his face.

Something was wrong. I just didn’t know what.

The last week of his life was a blur I didn’t recognize as foreshadowing until it was too late.

On Monday, he called and said, “I might be out of pocket for a couple days. Big deadline. If I don’t pick up, I’m not ignoring you.”

“Okay. I’ll assume you’ve been kidnapped by spreadsheets,” I joked.

On Tuesday, I texted him a photo of my dinner attempt gone wrong—blackened something that was supposed to be chicken. He didn’t answer.

On Wednesday, I called. Voicemail.

“Hey, it’s me,” I said lightly, even though something in my chest was tightening. “Just making sure you haven’t turned entirely into a computer. Call me when you come up for air. Love you.”

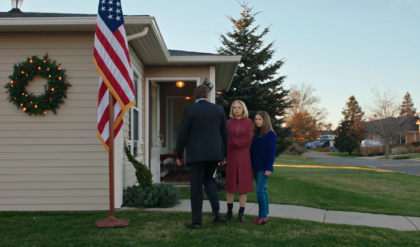

On Thursday morning, there was a knock on my door.

Two people stood on my porch. One wore a Northbridge polo shirt. The other had a badge clipped to his belt. I don’t remember the exact order of the words that came out of their mouths.

Incident at the office.

Paramedics called.

Couldn’t revive him.

We’re so sorry.

They said the official cause was cardiac arrest. Sometimes these things just happen. The man with the badge said he was young, yes, but stress, genetics, you never know.

I stood there in my hallway, leaning on the little table where I kept my keys and the bowl for loose change. Someone had put a vase of flowers there earlier in the week. They smelled too sweet.

“Can I see him?” I asked, my voice sounding far away to my own ears.

“I’m afraid he’s already been transported,” the man said gently. “We can give you the information for the medical examiner.”

I nodded like we were discussing scheduling, not my child’s body.

The man from Northbridge—Mr. Harris, his boss, I would learn later—kept saying how sorry he was.

“He was one of our best,” he said. “Dedicated, reliable. He carried a lot of weight.”

I wondered later if Mr. Harris realized how literal that sentence was.

The days after the funeral passed like I was underwater. People came and went. They brought casserles and pies and things you have to refrigerate but don’t want to eat. They told me stories about Daniel, how he’d helped them move or fix their computer or bought them coffee when they couldn’t afford it.

I nodded. I cried. I washed dishes I didn’t remember dirtying. At night, I lay awake and listened for footsteps that would never come again.

Three days after we buried him, I walked down to the mailbox. There was a stack of envelopes—bills, sympathy cards, a flyer for a pizza place—and a crisp white envelope with the North Bridge logo on it.

My heart fluttered.

Inside was a form letter.

Dear Ms. Lewis,

On behalf of everyone at Northbridge Data Solutions, we extend our deepest condolences on the passing of your son, Daniel Lewis. He was a valued member of our team and his dedication and work ethic will be missed.

There was a mention of benefits, final paycheck, HR contact information. At the bottom, in a different font, a note:

If you have any questions about Daniel’s role or our internal review of the incident, please contact—

The line ended in a blank space. Whoever had typed it had forgotten to fill in the name. Or maybe they didn’t know yet who would be brave enough to talk to his mother.

My phone rang that afternoon. The caller ID showed a number I didn’t recognize, but the area code matched the city.

“Hello,” I answered.

“Ms. Lewis?” A man’s voice. “This is David Harris. I’m—I was Daniel’s manager at Northbridge.”

I sat down at the kitchen table.

“Yes,” I said. “We met at my door.”

“I know this is a terrible time,” he said. “I’m so sorry to bother you, but I… there’s something I think you need to see. Something Daniel left behind at the office.”

My throat tightened.

“Left behind?” I repeated. “Like what? His mug?”

There was a pause.

“No,” he said quietly. “Not that. A file. A recording. Actually, more than one thing. I can’t explain it properly over the phone. Would you be willing to meet me at the office—or somewhere neutral if that’s easier?”

My first instinct was to say no. To say, Leave it. He’s gone. Whatever’s on his work computer is not my business.

But then I remembered the way he’d looked the last time he fell asleep on my couch. The dark circles under his eyes. The half-finished sentence.

We had a situation. I’ll tell you about it when it’s over.

What if this was the end of that sentence?

“What kind of things?” I asked. “Is he in trouble?”

“In trouble?” Mr. Harris repeated. And there was something like anger in his tone. Not at me. “No, Ms. Lewis. He’s not in trouble—but other people may be. And I think he meant for you to know what was happening, even if he never got the chance to send it.”

Send it.

I closed my eyes.

“All right,” I said. “I’ll come.”

“When?”

“Tomorrow morning,” he suggested. “I know getting to the office might be hard, but—”

“I’ll be there,” I said.

After we hung up, I sat at the table very still. Outside, someone’s lawn mower droned. Inside, my son’s ghost sat in all the things he’d never told me.

North Bridg’s building looked different when I knew my son had died inside it. It was tall, glassy, reflective, the kind of place that tries very hard to look modern and important. Last time I’d seen it, I’d been in the passenger seat of Daniel’s car, waving at him as he dropped me off at the front so I could see his desk.

This time, I took the bus and walked the last two blocks in uncomfortable shoes.

The lobby was too bright. There was a wall of faux plants and a receptionist who smiled politely without letting it reach her eyes.

“I’m here to see David Harris,” I said.

She checked a list and gave me a visitor badge.

“Take the elevator to the fifth floor,” she said. “He’ll meet you right there.”

The ride up felt longer than five floors. When the doors opened, Mr. Harris was waiting in the hallway. He looked different from how he’d appeared on my porch. Less corporate, more haunted.

“Ms. Lewis,” he said, extending a hand. “Thank you for coming.”

I shook it.

“Please call me Margaret,” I said. “Ms. Lewis makes me feel like I’m in trouble in school.”

He smiled faintly.

“Margaret, then,” he said. “If you’re ready, we can go to a conference room. I took the liberty of reserving one off the main floor, a bit more private.”

We walked past rows of cubicles. I tried not to look too closely at the faces peeking over monitor tops, the hands moving on keyboards. I wondered which of them had known my son, which had taken his mug from his empty desk, which had pretended not to see him drowning in work.

We sat in a small glasswalled room with a table and four chairs. On the table was a laptop and a folder thick with printed pages.

“I want to be very clear about something before we start,” Mr. Harris said, sitting opposite me. “Northbridge’s legal team would not be thrilled that I’m doing this. There’s an internal investigation going on. There will be statements and spin and all of that, but I… I have a son, not much younger than Daniel. I can’t sleep at night knowing what I know without giving you the full picture.”

My chest tightened.

“What picture?” I asked.

He opened the folder.

“I was Daniel’s direct supervisor for the last three years,” he said. “He was, without exaggeration, one of the most reliable engineers on my team. Smart, thorough, honest to a fault. When upper management wanted something done quietly that made the rest of us uneasy, they came to people like him because they assumed his loyalty was automatic.”

“That sounds like a compliment,” I said. “Until it doesn’t.”

“Exactly,” he said.

He took a breath.

“Six months ago, the company launched a new product,” he went on. “A big contract, tight deadline, lots of pressure from above. We were understaffed, but we were told to make it work.”

He slid a few pages toward me. Printouts of emails, words too small for me to absorb in a glance.

“As we got closer to launch, Daniel started noticing irregularities,” he said. “Data being moved from one server to another in ways that didn’t make sense. Logs being edited, security protocols bypassed by people with admin access.”

“By who?” I asked.

He pointed at a line on one of the emails. Names I didn’t recognize, but titles that made my stomach sink. Director. VP. C-level.

“He came to me first,” Mr. Harris said. “He said, ‘David, something’s wrong. I think they’re using our infrastructure to hide transactions for a client—or themselves. I’m not sure. But if anyone audits this, it’s going to look like we were complicit.’”

“What did you say?” I asked.

He looked ashamed.

“I told him to document everything,” he said, “and not to confront anyone alone. I said I would raise it with my boss, and I did. He told me to let it go. ‘Above our pay grade,’ he said. ‘Don’t go looking for a fight you can’t win.’”

He tapped the folder.

“Daniel didn’t let it go,” he said. “He started keeping his own records. Screenshots, copies of system logs, notes. He set up an encrypted folder off the main network where he stored everything. He also started drafting emails to our compliance department and eventually to an external whistleblower hotline.”

My hands were cold.

“You’re telling me my son was what? A whistleblower?” I asked.

“He was trying to be,” Mr. Harris said. “He was torn. On the one hand, he knew what it would mean to blow this open. People would lose their jobs. Massive clients could pull out. The company might retaliate. On the other hand, he had you. He had his own conscience. He used to say, ‘If my mom found out I knew about this and didn’t say anything, she’d tan my hide from beyond the grave.’”

A laugh burst out of me, sharp and painful.

“That sounds like him,” I whispered.

“It does,” he said softly. “Content of the message aside, he adored you.”

He turned the laptop toward me.

“The night he died,” he said, “we had a meeting with upper management. They’d found out about his concerns. Someone had seen his name tied to some of the system logs he’d pulled. They called us into a conference room, and let’s just say it was not pleasant.”

I saw a flicker of anger cross his face.

“They implied that if he didn’t ‘rethink’ his interpretation of the data,” he said, “his future at the company would be limited. They also hinted that if any of this got out, they knew he’d handled certain configurations and it would be easy to frame it as his error. ‘We all suffer if one person oversteps.’ That sort of thing.”

My stomach churned.

“They threatened him,” I said.

“They cornered him,” he replied. “I left that meeting feeling sick. I went back to my desk, ready to tell him we’d find another way, that I’d back him if he wanted to escalate anonymously. But he wasn’t there. I figured he’d gone to cool down. The next time I saw him, he was on a stretcher in the lobby.”

For a moment, the room spun.

He looked away.

“I can’t say stress killed him,” he said quietly. “I’m not a doctor. But I can say they put a weight on him that no one person should carry.”

He clicked something on the laptop.

“After he died,” he continued, “IT locked his accounts per protocol. HR had me pack up his desk, but something didn’t sit right with me. So I asked one of my guys, someone I trust, to make a copy of his user folder before they wiped it. I know that’s a violation of company policy. I don’t care.”

He opened a file. On the screen was a video player window, paused on the first frame: Daniel sitting in this very room, hair a little messier than usual, dark circles under his eyes, wearing the same North Bridge hoodie he’d asked about on the phone.

“Three days before he died, he recorded this,” Mr. Harris said. “He never sent it. It was saved as a draft email addressed to you. I think… I think he couldn’t bring himself to press send.”

My heart stopped.

“To me,” I whispered.

He nodded.

“Do you want to watch it?” he asked.

I wanted to say no. I wanted to keep my son alive in my head as the version of him I knew when he was still trying on suits in our living room. But I also knew I would never forgive myself if I didn’t.

“Yes,” I said. “Please.”

He hit play.

The video was vertical, like he’d propped his phone against something.

“Hey, Mom,” Daniel said. His voice was tired but soft. “If you’re seeing this, it’s because I chickened out and didn’t tell you this in person,” he went on, managing a crooked smile. “Or because something happened. Hopefully, it’s the first one.”

He rubbed his face.

“You always told me that doing the right thing matters more than keeping the peace,” he said. “Even if you lose things, even if you lose people. I hate that lesson right now.”

He glanced at the door as if making sure no one was listening.

“I found out some stuff at work,” he said. “Bad stuff. The kind of stuff that makes news when it blows up. They’re using our systems to hide transactions for a couple of clients who, let’s say, aren’t exactly paying their fair share. It’s not like I have a moral allergy to rich people saving on taxes, but this is different. This is illegal. This is people laundering money and pretending it’s optimization.”

He sighed.

“I thought if I documented everything and went through the proper channels, they’d fix it,” he continued. “You know, see something, say something. Turns out what they really mean is see something, shut up if you like your job.”

He laughed bitterly.

“They threatened to make it look like my fault if anything comes out,” he said. “Which is funny because I’m the only idiot trying to stop it. But they hold the strings. They can mess with logs, emails, narratives.”

He swallowed.

“I’m scared, Mom. Not of losing the job, honestly. I can work somewhere else. I’m scared of dragging you into a mess. I’m scared of dying on some hill that nobody else even sees as a hill.”

He paused.

“If I back down,” he said slowly, “I have to live with knowing I saw something wrong and walked away. If I push, I might blow up my life and make you suffer indirectly. There’s no version of this where I feel noble. It all feels heavy.”

He looked into the camera.

“I’m not telling you this so you’ll tell me what to do,” he said. “You’d probably tell me to get a lawyer and a good night’s sleep. I’m telling you because if something happens and they put my name on some report saying I acted alone or made an error in judgment, I want you to know that’s not the whole story. I tried, Mom. I really did. If I failed… I’m sorry.”

His eyes glistened.

“You told me once that whatever I do, you’ll be proud of me as long as I don’t lie to myself,” he said. “I’m trying to hold on to that.”

He swallowed again.

“Anyway,” he said, forcing a smile. “This is getting long. I’ll probably delete it in the morning and tell you over coffee like a normal person. But if I don’t… I love you. Please don’t think I was a coward either way. Sometimes the right thing is not clear until way after the credits roll.”

The video ended.

The room was silent except for the faint hum of the air conditioning. My cheeks were wet. I hadn’t felt the tears start.

“He never showed me this,” I whispered.

“I know,” Mr. Harris said softly. “But he left it. And he labeled that folder in a way that makes me think he wanted someone to find it.”

“What did he label it?” I asked.

He turned the laptop so I could see the file path. At the top, a folder name:

for mom. If anything happens.

My vision blurred. I pressed my hand to my mouth.

“He knew,” I said. “He knew something could happen.”

“He knew there was a risk,” Mr. Harris said. “And he took it anyway. He pushed the folder toward me. “These are the documents he collected,” he said. “The logs, the screenshots, the drafts of his reports to compliance. I’ve made copies. I’ve also taken them to an external lawyer. There will be investigations now that go beyond what Northbridge can manage internally.”

I stared at the stack of papers.

“And the company?” I asked. “What are they saying?”

He looked tired.

“Officially, they’re mourning the loss of a valued team member and conducting a ‘routine review,’” he said. “Unofficially, some people upstairs would be happy if all of this stayed buried and Daniel took the blame as a rogue employee who mishandled systems. I won’t let that happen. Not now.”

“Why now?” I asked quietly. “Why not when he first came to you?”

He flinched.

“Because I was a coward,” he said simply. “Because I told myself I had a mortgage and a kid in college and that it wasn’t my fight. Because I thought maybe he was overreacting or that someone else would step in. I was wrong. And now he’s gone and I can’t undo that. But I can do this.”

We sat there for a long moment.

“I can’t bring him back,” he said. “But I can help clear his name. And I can make sure the woman who raised him knows he died trying to be the person she taught him to be.”

I looked at the picture on the screen—my son, tired but honest.

“Thank you,” I said.

And for the first time since the day he died, I meant it when I said those words to someone from that building.

It took months. Lawyers, investigations, whistleblower reports, anonymous leaks to a journalist who showed up on my porch one afternoon and asked if I would talk about my son. I didn’t tell them everything. Some pieces of Daniel belong only to me. But I gave them enough. Enough to make sure any article that ever mentioned his name also mentioned the words scapegoat and retaliation and corruption.

Northbridge eventually issued a statement. They called it “a breakdown in internal controls.” They talked about “a complex situation involving a small number of executives who breached our trust.” They did not say, “We tried to bully a young engineer into carrying the moral weight of our crimes.”

But they did say this:

Contrary to initial assumptions, we have found no evidence that Daniel Lewis initiated or led any improper activity. In fact, his internal communications indicate he raised concerns and attempted to prevent such activity. We regret any implication otherwise and extend our apologies to his family.

They offered a settlement. Money to “trip you.” I took it. Not because you can buy back a life. You can’t. But because I knew Daniel would want me to use every tool available to make sure I could live without having to ask anyone for help with my electric bill ever again.

With part of it, I set up a scholarship at his old high school—the Daniel Lewis Memorial Award. The plaque reads:

For a student who tells the truth even when it costs them.

At the first ceremony, I stood on a stage in a gym that smelled like old sneakers and hope. A nervous 12th grader named Ashley came up to accept the certificate.

“Your son sounds incredible,” she whispered when we shook hands.

“He was,” I said. “So are you, for standing up to that teacher who changed your grade because you wouldn’t cheat.”

She blinked.

“Wait, how did you—?”

I smiled.

“Adults talk,” I said. “Sometimes the right ones listen.”

People sometimes ask me if knowing the truth about Daniel makes it easier or harder to live with his death.

The answer is both.

It hurts to think about the weight he carried alone. About the nights he sat in that glasswalled room recording videos he never sent because he didn’t want to worry me. It hurts to know that doing the right thing might have shaved years off his life.

But it heals something deep to know that my son did not die a coward. He did not look away. He did not quietly fold himself into a shape that made powerful men comfortable. He tried—right up until his heart gave out or his body decided it had had enough.

He tried to tell the truth, and when the systems around him chose to crush him instead of listen, he still thought of me.

For mom, if anything happens.

That folder saved his name. Maybe in a way it saved mine, too.

If you’ve stayed with me to the end of this, thank you. I know this wasn’t a light story. It’s not something you put on in the background while you fold laundry and forget five minutes later. But I think it’s important, because somewhere out there right now, another Daniel is sitting in a conference room being told to rethink his ethics. Another Margaret is wondering why her child sounds so tired on the phone. Another boss is deciding whether to be a coward or a person.

If you’re the one carrying the secret, please document everything. Tell someone you trust. Don’t let them turn you into a villain in your own story.

If you’re the parent, ask the extra question. Don’t just say, “How’s work?” Say, “Are they asking you to be someone you’re not?”

If you’re the boss, like David Harris—remember that silence is a decision. Doing nothing is choosing a side.

Now, I want to hear from you. Have you ever found out after someone died that the story everyone told about them wasn’t true? Have you ever seen a good person turned into a scapegoat to protect people with more power? Share your story in the comments. You never know who might read it and realize they’re not alone—or who might find the courage to open their own “for mom, if anything happens” folder.